"Οι καιροί της Κύπρου".

Κέντρο Ευαγόρα Λανιτη, Λεμεσός, 17/11-17/12/2010

Επιμέλεια έκθεσης ; Αντώνη ΔΑΝΟΣ, λέκτορας ιστορίας και θεωρίας της τέχνης, τεχνολογικό πανεπιστήμιο Κύπρου.

ISBN 5 292084 171119

Κυπριακή πολιτική και καλλιτεχνική εφημερίδα, Λεμεσός 17/11/2010, Έτος 50ό, σελίδα 3, «There will be no homecomings» :

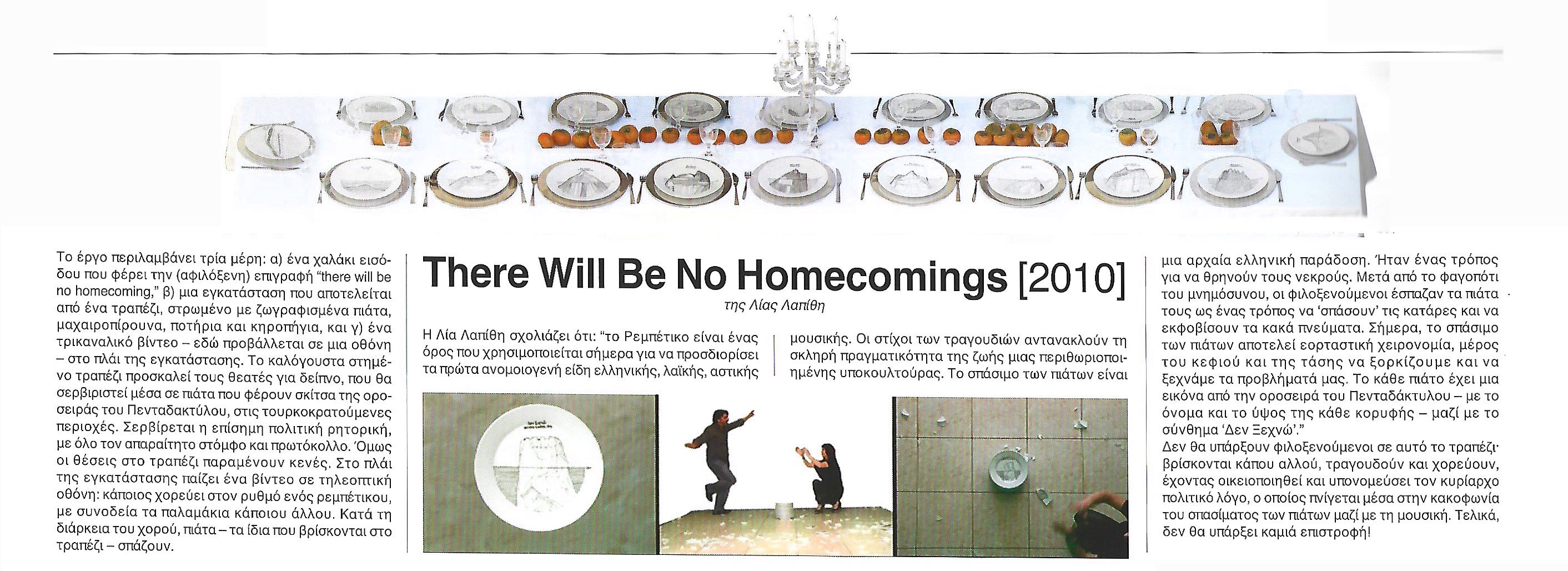

Η εγκατάσταση έργου αποτελείται από τρεις άξονες -

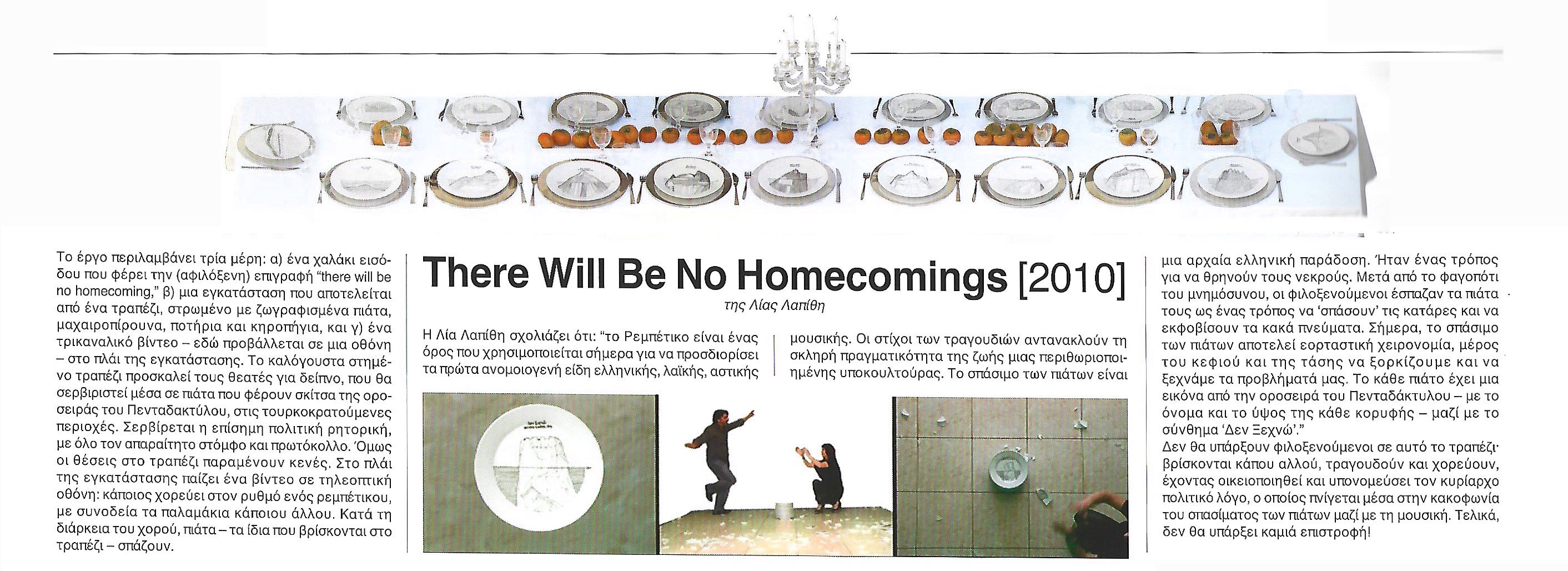

1. Τραπέζι στρωμένο με 19 ζωγραφισμένα πιάτα που απεικονίζουν βουνοκορφές του Πενταδακτυλου

2. Λωτούς (το μυθικό φρούτο)

3. Χαλάκι εισόδου με την φράση There will be no homecoming, τυπωμένη για να διαβάζετε για οποίο μπαίνει η βγαίνει

Σημείωση- το χαλάκι αυτό έχει φωτογραφηθεί σε διαφορά σημεία στην Πράσινη Γραμμή της Λευκωσίας, όπου η είσοδος και έξοδος της είναι στρατιωτικά ελεγχόμενη και απαγορευμένη.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

There will be no homecoming:The word "homecoming" to the viewer has distinctly-different symbolic implications… The words are mirrored for both parts. To go, to come back, insiders/outsiders, whose home is it and what does homecoming mean? This piece is dedicated to all those people who have had to leave there home (immigrate) and could not making it back home, but mostly to my father, age 87, who was born on Pendadactylos Mountain, and since 1974 has been longing to return to his home. Many of his friends have died waiting.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Re-visiting the Lost Home: There will be no Homecoming

Domesticity and the usage of uncanny objects have been used extensively in feminist art. Since the 1970s women from all around the world have staged domestic settings where with irony and humour have challenged the prevailing patriarchal convictions. Women artists from the Middle East have produced powerful works that use domestic objects as politicised “un-homely devices” to challenge patriarchal stereotypes, and to address socio-political issues.

Lia Lapithi (b.1963) is a Greek Cypriot multidisciplinary visual artist who explores in her work the concepts of home, exile, and belonging in contemporary Cyprus. Her practice spans photography, video, sculpture, installation and performance.[1] In 2013 she produced the work There will be no Homecoming, which displayed a printed doormat in two different locations at Cyprus’ divided capital, Nicosia.[2] For this project, the artist had imprinted the words ‘There will be no Homecoming’ that are mirrored on the doormat. She then positioned the doormat on two locations in the old city of Nicosia: one at the UN (United Nations) Sector 2 controlled buffer zone and the other one at a Greek Cypriot military guard post. The situation of the two locations is significant as Lapithi chose to make an artistic intervention in an environment that has been predominantly controlled by masculinised politics.

When strolling along the old city of Nicosia, one will face streets that end with barriers and barbed wires. The city is divided by the Buffer Zone; a zone that is guarded by the United Nations and separates Greek Cypriots to the South and Turkish Cypriots to the North of Cyprus. Yael Navaro-Yashin (2003: 115) describes the experience of strolling in Nicosia’s streets as ‘walking through a half-dead city’ where the houses are abandoned and ‘space is kept unkempt, ruins of war are unrepaired, [and] wrecked buildings are left intact’.

Lapithi’s wording ‘there will be no homecoming’ reflects the important changes Cyprus underwent in the past decades. In 2003, the authorities of the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) opened the Green Line borders and for the first time since 1974, citizens could travel to the other side. Prior to that and for nearly thirty years, the Green Line was a closed border and crossings without permission were not allowed between the two communities. During the first weeks of the opening of the border thousands of people visited their home of origin where the faced the painful reality that their homes were now occupied by someone else. Lapithi talks about this experience:

‘My home (or family home) has been sold by the occupation regime without our consent. After the ‘Green Line’ crossing opened, many visited their houses as ‘guests’ and this continues to this day, Greek Cypriots visit their houses as ‘guests’ to Turkish nationals and/or Turkish Cypriot living in their houses, and Turkish Cypriots have similar experiences. This remains a surreal situation for people from both sides’.[3]

Lapithi’s words reflect the journey many refugees had experienced during their “return”. During the post-1974 time they spent in exile, refugees trusted their hopes into what became to be a “myth of return”. This myth was based on the memories and accounts of what they lost in 1974: their homes, lands, community, and sense of place and belonging. The “myth of return” was a central theme of Greek Cypriot politicians who insisted for decades that any political settlement to the Cyprus’ Problem would ensure the return of refugees to their properties. Lapithi represents in There Will be no Homecoming the reality that refugee faced after the opening of the crossings, that the ‘assured return’ might not be feasible.

Feminist academic and activist Maria Hadjipavlou talks, in a dialogue with Lapithi, on her return to her parent’s house:

‘It is even worse because I realise it is not only the physical space that is occupied by complete strangers from another country (Bulgarian Turks) who I assume are indifferent to my story and emotional connection but also I experience this double bind. Unknowingly, these strangers have invaded my memories, my own private world which they could not ever know. I go and I find them using what I am not allowed to have as a consequence of force. I feel angry, ambivalent, sad, embarrassed, empathic to the other, and keep hoping that one day we shall find a resolve to what ‘filoxenia’ [Greek for hospitality] means in a situation where I the real owner feels a stranger and an intruder!’[4]

According to Maria Hadjipavlou, the property issue is ‘the most complex and significant one in the Cyprus conflict because of its connection to identity, justice and family history’.[5] The same space, a house, symbolises past and present realities for both parties, ‘guests/visitors’ and ‘owners’. Hadjipavlou offers testimony of an exchange between two men after a Greek Cypriot owner visited his home, which post-1974 was inhabited by a young Turkish Cypriot family:

GC: This is my home. I was born and I lived here until 1974 when I was 23. I want to return and have my property back.

TC: This is my house too. I was born there thirty years ago and I want to live here on this side. I feel it home too.

Lapithi’s work exposes the complicated property issues experienced in contemporary Cyprus. The experience of crossing the border discloses the reality that there are no feasible homecomings to one’s home of origins. Lapithi dedicates this work to the people who were forced to leave their homes and cannot return. Since the opening of the borders, Lapithi tried many times to visit her occupied home:

‘I could never make it past the doormat. My family home was sold illegally, and without my knowledge or consent, to a British lady as a vacation home. She painted the doors and windows blue (resembling Greek islands) and put double locks everywhere, as well as a no trespass sign.’[6]

The words ‘there will be no homecoming’ was an overarching theme in several of Lapithi’s works. However, she soon realised that the words disturbed some people, as they found them to be provocative and depressing; they felt the title implied that there is no hope of returning and they had to accept the possibility of no return.[7] It is obvious here how the myth of return still resonates with people even after the opening of the borders and the realisation that someone else lives in their homes.

Lapithi’s Doormat recalls Mona Hatoum’s 1996 Doormat, made of stainless still pins that form the word ‘welcome’. Both artists have modified a domestic object into an uncanny one that is no longer homely and familiar. The usage of the words ‘there will be no homecoming’ and ‘welcome’ expose the reality they face as exiled artists who are no longer welcomed to their home of origin. Their doormat constructions can be seen as “un-homely devices” as they represent a place where one is no longer welcome and ‘homeliness’ is now threaten by someone else’s presence into that space.

The Greek Cypriot and Palestinian communities share some similarities in the ways they experience their return visits to their occupied homes. Their visits become politicised activities in re-claiming their lost home. When they visit their occupied villages, they engage in an extremely emotional pilgrimage where they visit the graves of family members and place flowers on them. They also visit their orchards and gardens where they pick fruit and bring pots of soil back with to preserve and cherish with their families. Plants and trees are significant to the exilic experience as ‘do not solely bear a “sensual” presence but also an existential one; they preserve the ownership, property, continuity, existence and analogy of the person.’[8] For Greek Cypriots, orange and citrus trees are crucial elements of their exilic narratives. Similarly, olive trees became a national symbol in Palestinian stories and poems after 1948. [9] The act of replanting seeds and trees is highly politicised because it enables a temporary re-claim of the lost home and evokes a symbolic association to the homeland.

[1] Lia Lapithi’s work has been widely shown in international exhibitions and her portfolio includes the collaboration ‘From Khirokitia to Mars’ at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. See http://www.lialapithi.com for the full range of her work.

[2] The doormat was previously exhibited at the 2010 Looking Awry: Views of an Anniversary Exhibition in Cyprus. The exhibition was held as a celebration of the 50 years of the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus and aimed to exhibit works that examined Cyprus’ recent past, present, and possible futures. Lapithi’s part included the installation Olive Bread and Retro Plates, the video Rembetiko, and the doormat.

[3] Lapithi 2011, Nineteen Mountain Peaks and a Dinner, Nicosia: Cassoulides. p. 8.

[4] Lapithi Lia. http://www.lialapithi.com/Guest.htm.

[5] Hadjipavlou, Maria. ‘Multiple Stories: The 'crossings' as part of citizens' reconciliation efforts in Cyprus?’, in Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, Vol. 20, Issue 1, 2007, pp. 53-73, p. 64.

[6] Email communication with Lia Lapithi.

[7] Email communication with Lia Lapithi.

[8] Cyprus and the politics of memory p.135

[9] Ben-Ze’ev 2004 p.143